What are human prion diseases?

This post is part of a series introducing the basics of prion disease. Read the full series here.

Prion diseases are a group of neurodegenerative diseases caused by prions, which are “proteinaceous infectious particles.” For some background, first see this introduction to prions. Prion diseases are caused by misfolded forms of the prion protein, also known as PrP. These diseases affect a lot of different mammals in addition to humans – for instance, there is scrapie in sheep, mad cow disease in cows, and chronic wasting disease in deer.

The human forms of prion disease are most often the names Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), fatal familial insomnia (FFI), Gertsmann-Straussler-Scheinker syndrome (GSS), kuru and variably protease-sensitive prionopathy (VPSPr). All of these diseases are caused by just slightly different versions of the same protein, so we refer to them all as prion diseases.

Even though prion diseases do come in slightly different forms, they have a whole lot in common. In each disease, the prion protein (PrP) folds up the wrong way, becoming a prion, and then causes other PrP molecules to do the same. Prions can then spread “silently” across a person’s brain for years without causing any symptoms. Eventually prions start to kill neurons, and once symptoms strike, the person has a very rapid cognitive decline. Most prion diseases are fatal within a few months, though some can last a few years [Pocchiari 2004].

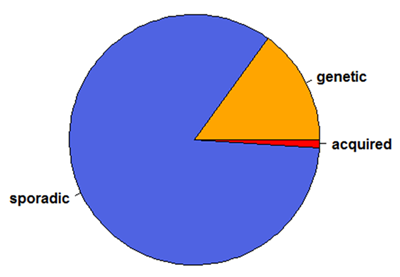

Prion diseases in humans are fairly rare – about 1 to 2 people out of every 1 million people dies of a prion disease each year [Klug 2013]. Prion diseases can come about in one of three ways: acquired, genetic or sporadic.

Acquired means the person gets exposed to prions and becomes infected. Even though prions are scary, they’re very hard to catch, and so infection is the least common way of getting a prion disease. There was a famous epidemic of kuru, a prion disease which was passed from person to person by cannibalism, in Papua New Guinea, but this has now mostly subsided. Then there is mad cow disease or bovine spongiform encephalopathy. This disease passed from cows to humans through contaminated food. The human form of the disease is called variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (vCJD) and has killed about 200 people in the U.K. since 1994 [UK CJD Survelliance]. Today there are only a few people are dying of this disease each year. There have also been cases where prion disease has been transmitted via contaminated surgical instruments, human growth hormone supplements, or transplants of dura mater (a tissue surrounding the brain). These medical infections are called “iatrogenic” infections.

Prion diseases can also be genetic. First, let’s recall some biology basics. DNA contains instructions which get re-written in RNA, and then the instructions in RNA get translated into protein. So changes in a person’s DNA can cause changes in the proteins their cells produce. Everyone has a gene called PRNP which codes for the protein called PrP, and most of the time this protein is perfectly healthy and fine. Some people have mutations in the DNA of their PRNP gene, which cause it to produce mutant forms of PrP. These mutant forms don’t form prions instantly, and most people with PRNP mutations live perfectly healthy for decades. But as people get older, the mutant forms of PrP are more and more likely to fold up the wrong way and form prions. Once they do, the person has a rapid neurodegenerative disease.

Some people refer to genetic prion diseases as “inherited” or “familial” prion diseases. We prefer not to use these terms: just because a disease is genetic doesn’t mean it’s inherited or familial. Every DNA mutation has to start somewhere, so some people with genetic prion disease are the first in their family – they didn’t inherit the mutation, and it’s not familial. According to one estimate, 60% of genetic prion disease patients have no family history of the disease [Bechtel & Geschwind 2013].

Finally, prion diseases can simply be sporadic, meaning we don’t know why they happen. Some people think that sporadic prion diseases happen when one prion protein just misfolds by chance, and then spreads from there. Others think that the disease may start with one cell that has a spontaneous DNA mutation and starts producing mutant PrP. We don’t know what the real answer is. Either way, the effect is that people with no previous exposure to prions and no mutations in (most of) their DNA end up getting a prion disease out of nowhere.

The sporadic form of prion disease is by far the most common. It’s often estimated that human prion disease cases are 85% sporadic, 15% genetic and < 1% acquired [Appleby & Lyketsos 2011, CDC Fact Sheet, UCSF Primer].

So prion diseases can be categorized by where they came from: acquired, sporadic, and genetic. But as mentioned at the top of this post, you’ll also hear prion diseases categorized a different way, most often as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), fatal familial insomnia (FFI), and Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker (GSS) syndrome. The origin and use of these names can be confusing. The names were originally used to categorize patients by their symptoms, but later came to refer to particular strains or genetic varieties of prion disease.

For instance, the name fatal familial insomnia was originally applied to a family with a genetic disease with insomnia as the first and foremost symptom [Lugaresi 1986]. After it was later found that a particular genetic mutation caused this disease [Medori 1992], people started using FFI to refer to the disease caused by that one particular mutation, even though for some patients insomnia isn’t a major part of the disease [Zarranz 2005]. Later on scientists discovered a non-genetic form of FFI and called it sporadic fatal insomnia (sFI) [Parchi 1999], but other people see it as a subtype of CJD and refer to it as “MM2 thalamic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease” [Moda 2012].

To add another layer of complexity, new types of prion disease are still being discovered that don’t fit into any of the original three categories (CJD, FFI or GSS). For example, the most recent new form was dubbed “variably protease-sensitive prionopathy” (VPSPr) [Zou 2010]. That’s quite a mouthful.

Since the naming system can be confusing, we usually avoid it altogether and simply refer to all of these diseases as prion diseases. For genetic prion diseases, it is useful to name the exact mutation – for instance, E200K or P102L (for how to interpret these numbers and letters see our upcoming primer on genetic prion diseases). As for sporadic prion diseases, scientists have a system of biochemical subtypes such as “MV1″, “VV2″, “MM2 cortical” and so on.

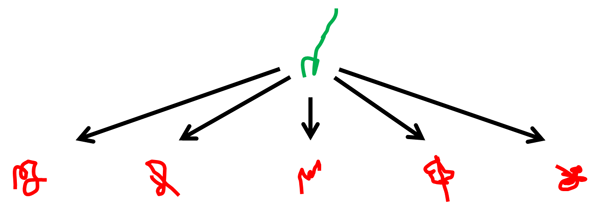

One of the surprising things about prion protein is that this single protein can fold up in so many different ways that are toxic and cause disease. The diagram below illustrates how just one protein – PrP (green) – can fold up in several different ways, creating several different strains of prion (red).

There are actually a dizzying number of different forms of human prion disease. Kuru and vCJD, two strains that people have acquired by infection, are probably the most famous but also the most rare. There are also at least 6 strains of sporadic prion disease [Parchi 2011] and over 40 genetic mutations that cause prion disease [Beck 2010].

Many of these different prion strains act pretty differently. They come from different sources, cause different disease symptoms and strike people of different ages. But since they’re all caused by the same protein – PrP – we’re hopeful that it will be possible to find one treatment that will treat all of these different diseases.